While I have many chapters to write, I believe this one will be among the hardest. It reveals to me my biggest failing. By the time I had turned 18 and could leave home, I had endured so much family-induced trauma that all I wanted to do was escape. Later on, I had an epiphany and tried to reconnect, but despite all my efforts, I couldn’t mend the damage that had been set in motion decades ago and further compounded by the constant flow of man made disasters and crises that have befallen myself and the rest of the human race on a regular basis. The result is that I failed at the one thing that might have brought me some closure on my tragic family legacy. I failed my Grandmother and Grandfather; I’ll address that later.

To kick things off and set the tone for a lifetime committed to raging against the machine, here’s a short film I created titled A Brief History of Calamity. It’s my tribute to the anthropogenic disasters that have shaped, impacted and destroyed human lives since 1900.

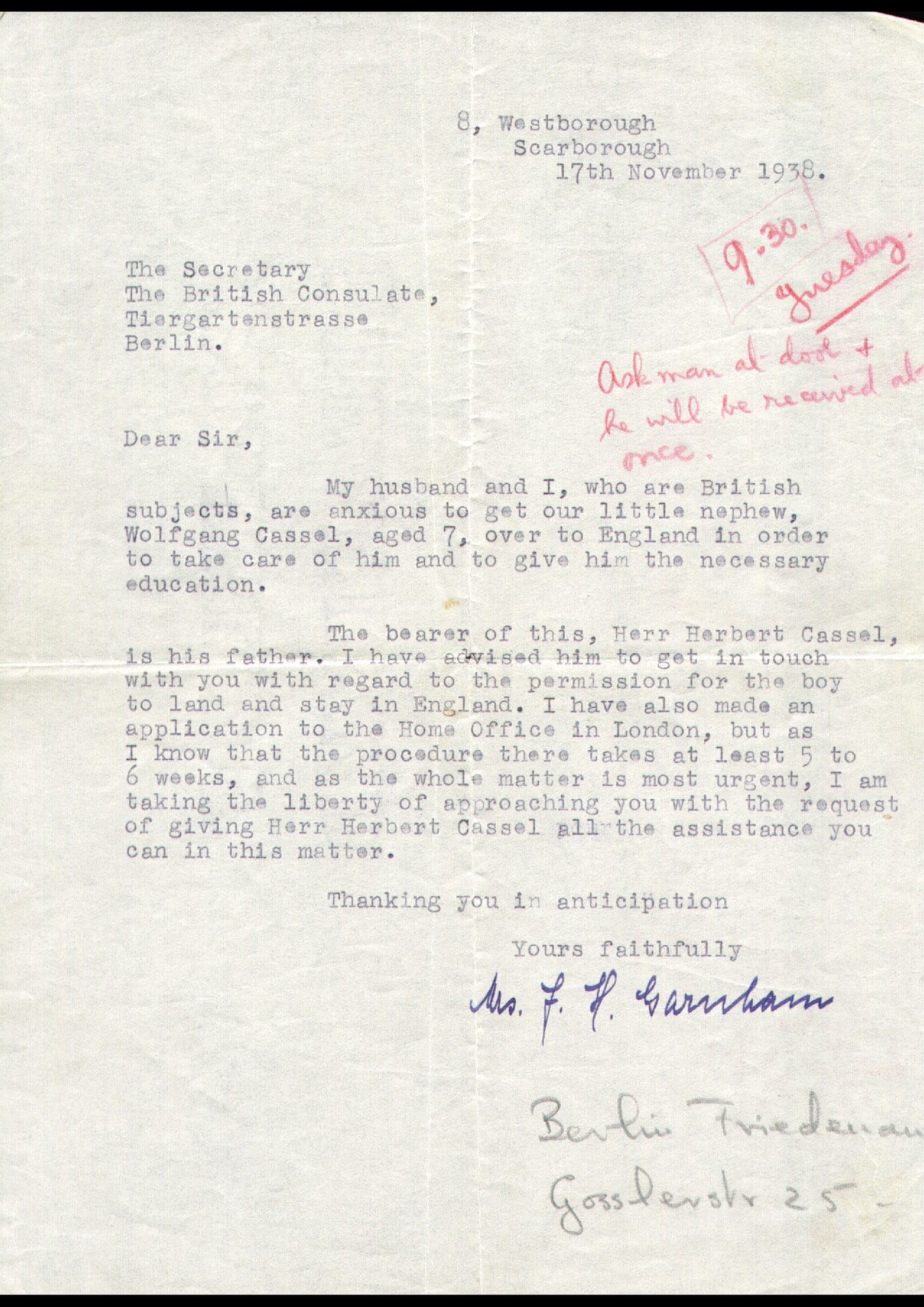

1938 - Sanctuary

Shortly after Hitler rose to power, my Great Aunt Hilda became deeply unsettled by the political changes in Germany. Anticipating the worst, she moved to England in 1933 to assist any family members who wanted to leave. She became 'The Exit Strategy.' At the time, no one else seemed particularly concerned. 'Don’t worry, it will be fine,' they all said. But she had been paying attention for a long time, and it was her foresight that taught me to read the writing on the wall early in life and always be prepared to leave if things got too hot or unpredictable.

It is because of her and her wisdom that I am here. The onslaught mounted by the German people was pervasive.

In their 25-point party program published in 1920, Nazi Party members publicly declared their intention to segregate Jews from “Aryan” society and to abrogate their political, legal, and civil rights.

Nazi leaders began to make good on their pledge to persecute German Jews soon after their assumption of power. During the first six years of Hitler's dictatorship, from 1933 until the outbreak of war in 1939, Jews felt the effects of more than 400 decrees and regulations that restricted all aspects of their public and private lives. Many of these were national laws that had been issued by the German administration and affected all Jews. But state, regional, and municipal officials, acting on their own initiatives, also issued many exclusionary decrees in their own communities. Thus, hundreds of individuals in all levels of government throughout the country were involved in the persecution of Jews as they conceived, discussed, drafted, adopted, enforced, and supported anti-Jewish legislation. No corner of Germany was left untouched.1

The Nazis seemed intent on causing harm to the Jews in any way they could—if not through death, then through intergenerational tyranny. If they couldn't eliminate the entire family now, they could still destroy it over time by eroding familial bonds and psychologically dismantling individuals. It just takes time. Those who harbor hate will stop at nothing to impose harm. In an unregulated world, this is a dangerous and insidious threat.

My father arrived in England on December 23, 1938, where he was met by Aunt Hilda and her husband, Mr. Garnham. They took him home and raised him as if he were their son, never having children of their own. I never came to know what her husband’s first name was.

Great Aunt Hilda passed away at 84, when I was 15. She had been living alone on the other side of the world in Australia, with no extended family and few friends. She reportedly took her own life with sleeping pills, leaving behind a note that spoke of her overwhelming loneliness. She was ultimately killed by the very isolation and despair spawned by the madness of those who sought to exterminate entire families.

My father loved Auntie Hilda as a mother and was devastated when he got the news of her death—and the way she died. When it happened, he too was living alone with no extended family around him. I never had the chance to ask her all the questions that have since formed in my mind, like, "What was your husband's name?" and "When exactly did you leave Germany?"

There are significant gaps in my family history and childhood memories that weigh on me, sometimes leaving me feeling profoundly incomplete.

In England, Henry encountered other children who targeted him for being German. For a time, he was unable to speak English. The kids at school would taunt him with labels like 'Nazi' and 'Jewboy,' completely unaware of the irony in their words, as they failed to understand his true situation.

In an effort to assimilate, he, like Ernest Cassel, anglicized his name to something distinctly British: Henry Walter Cassel. About six months after his arrival, he had a good grasp on English and completely pushed the German language out of his mind. He later told me that he wanted nothing to do with Germany, and as an adult, he was unable to speak the language, except for a few words related to foods he had enjoyed as a child.

All family members who remained in Germany were exterminated in Nazi death camps. Despite this, he managed to grow up with a mother and father figure who loved each other and took care of him as their own. During his nine years in England as a refugee, he was classified as an 'enemy alien,' required to sign in at the police station weekly, and was not allowed to have a passport.

In 1947, when Henry was 16, Hilda had located his mother, Lotte, her sister, and arranged for the two of them to be reunited. Henry was sent to Australia on a special one-time travel visa, never to return to England.

While on the ship, he met girls and apparently smoked 3 packs of cigarettes a day. He told me that the 3 month voyage was mostly a party.

Immediately upon landing, he was again classified as an 'enemy alien' by the Australian government and was again required to sign in at the police station weekly. After his arrival, he was reunited with his mother, who had married an Orthodox Jew.

She insisted that, to stay in her house, he must complete his Jewish studies, undergo the bar mitzvah, and accept the Jewish faith. Henry refused, saying, 'After what happened to the family… are you out of your mind?' Six months later, he was kicked out of her house, leaving him homeless, stateless, and without a passport for the next five years.

After the war, one of the primary impacts of the Holocaust on Jewish families was widespread fragmentation.

Years often passed between separation and reunification, during which many children and parents lost their emotional bonds as well as shared cultural and linguistic connections.

In many cases—including my own—this ultimately led to feelings of disenfranchisement, resentment, and displacement.

Finding a place in a community and having the support of family becomes integral to success. Without those foundations, everything depends on chance.

Upon leaving his mothers’ house, his immediate solution to the accommodation question was to sign up with The Royal Victorian Scottish Regiment based in Melbourne so that he could secure housing, meals and a purpose. He had to pass time until he was of legal age.

As it turns out, my father wasn’t very good at soldiering. He had been tasked with learning the bagpipes and failed miserably. He also told me that he couldn’t get used to wearing a kilt. I never did ask him if it was true, you know, about the “what’s under the kilt thing”. He left the Regiment about a year later after which time he worked a variety of odd jobs and rode around on motorcycle.

In 1952 Henry was finally granted statehood in the form of an Australian passport. With his new found freedom, he immediately left for Canada, by ship, to explore career prospects in the oil industry.

He moved around a lot until he found work at the Dunlop Rubber Company in Toronto, Ontario, as a stockroom assistant. In a few short years, he was promoted to stockroom manager. While in that position, he took it upon himself to completely redesign the warehouse to improve efficiency. This initiative caught the attention of upper management and eventually led to a regional sales management position, which took him from one end of the country to the other as he set up new clients and sales routes. The majority of his new clients were Oil companies that needed to put industrial strength tires on their heavy machinery.

My dad was a jet setter, flying all over the place seeking out new clients. His business trips frequently took him to Vancouver, British Columbia where he would rent a car and drive around the province looking to sign new customers.

He always rented his cars from Avis and, on one occasion, he rented a car from the woman who would end up being my mother, Grace Cassel. He didn’t waste any time asking her out and soon they were engaging in a long distance romance. He would communicate with her about when she was working at the Avis desk so that he could always be sure to meet up with her on his arrival.

Eventually, Henry was promoted to Sales Manager for the province of British Columbia. He settled into an apartment in Vancouver, which brought him into daily contact with Grace, and their romance quickly flourished. It wasn’t long before she invited him to her hometown—a tiny Ukrainian village called Smoky Lake, Alberta—to meet her parents and family and announce their plans to marry. Grace was 19, ten years younger than Henry.

My mother’s family—my family—was enormous! It all began with the Kulchisky and Rosychuk families, who emigrated from Ukraine and settled in Smoky Lake, a small hamlet 110 kilometers north of Edmonton, Alberta. Remarkably, they had moved halfway across the world only to settle at a latitude that provided a climate strikingly similar to the one they had left behind. Yet they didn’t seem to mind the harsh winters, with temperatures plunging to minus forty degrees. They were farmers and so the land was workable enough for them to be able to put down roots.

In the spring of 1899 over thirty families left their small Ukrainian village of Toporiwtsi, situated in the county of Chernovtsi, in the province of Bukovina. Their destination was “Kanada” and their goal was the fulfilment of a dream not clearly discerned but embracing a vague optimism of something better than they had yet known. Their courageous venture encouraged another group to follow in 1900, and a subsequent, larger group in 1902. There was justification for their decision. The life they were about to leave was dimmed with drudgery. Although the shackles of serfdom were being eased, poor agricultural conditions, shortages of land, and continued redistribution of land among family members, projected a life of poverty and hardship deep into the future. Employment was menial, rewarding only a meagre subsistence, and education, the vehicle by which to escape an impoverished life, was an unattainable reality. However, rumor of “free land, wide fields and open prairie as far as the eye could see” offered encouragement. Letters from earlier settlers in the Egg Lake district (Andrew, Star, Wostok) confirmed the rumor, while land agents reinforced similar accounts. Amid such circumstances they chose to place their faith in the hands of providence and embark in quest of a brighter future.

They left behind family and friends, often the wife or children, their established traditions, and their village with its straw thatched, mud plastered, white washed homes cloistered around a Greek Orthodox Church the fountain of their faith, and they took with them an unrelenting determination to meet the vast expanse of “unknown” with hope and courage.

The trek from Toporiwtsi was far from easy. An immediate handicap was language. Knowing only Ukrainian they faced impatient, uncomprehending, and often unscrupulous immigration officials, Their voyage from Hamburg, Germany to Halifax was a two week ordeal and many were overcome with regrets and homesickness. The train trip from Halifax to Winnipeg, the Immigration Centre to the West, and finally to Strathcona, South Edmonton, completed the first phase of their sojourn half way around the world.

The next phase was probably more traumatic. With their small initial savings nearly exhausted, they stood on the threshold of the “vilni zemli” with fear, uncertainty, and flagging spirits. 2

Once in Canada, my great-grandparents from the Kulchisky and Rosychuk families were remarkably prolific when it came to growing the family.

Russell Kulchisky (1918 - 2008) andAnne (Annie) Rosychuck (1921 - 2016) lived from birth to death in Smoky Lake. They got married back when they were both still extremely young.

Russell had 2 brothers, Alex and Metro and one sister, Steffi. Annie had a massive family, 3 brothers, William, Eli and John and 5 sisters, Mary, Rachael, Olga, Rose and Lucy. I only really remember Lucy. I met her twice. When I first met her she had a flaming red beehive hairdo, cat eye glasses and smoked like a chimney. She smoked so much she sounded like one of Marge’s sisters on The Simpsons. She was a living cartoon, larger than life, the center of attention.

My mother, Grace, was born into a farming family with five uncles and six aunts. There was always a party at her parents’ farmhouse. My grandparents, Russell and Anne, started a polka band called the Dyna Tones and were always playing at family weddings and holiday celebrations. Russell played the saxophone, and yes my Grandma, Annie, played the drums! My mother grew up surrounded by music and people. Music was so important to them that they had their instruments engraved on their headstones.

Interestingly, in 1960—the year before I was born—my grandmother had another child, my mother’s sister, Dale. When I finally met Dale, she was introduced to me as my aunt, which felt strange since we were nearly the same age. Dale was a devoted daughter and stayed with her parents on the farm almost until the end of their lives. After Russell and Anne passed away, she married a local man Larry Just, but tragically, she died of heart failure in 2020 at just 59 years old thus effectively ending the Kulchisky line.

I think my father was a bit overwhelmed by the size of my mother’s family, having never experienced such a large family in his own life. My parents came from completely opposite backgrounds, which, I believe, goes a long way in explaining what eventually happened to their relationship—and, ultimately, to me. My exposure to this side of my family was extremely limited.

From the moment they got married, my dad was on the road. When my mother became pregnant with me, he was still mostly away for work. When it came time for my delivery, he was, once again, on the road. He told me he made it back just in time to witness my birth. They had been living in Calgary, Alberta, for a few months, but as soon as I was born, they were on the move again. They eventually settled in Bay Ridges, a suburb of Toronto, right next to the Pickering Nuclear Power Station.

I often muse that my superpowers come from the radiation created by the plant I grew up around.

My dad purchased a townhouse in a subdivision and then went off to work, sometimes for weeks at a time, leaving my mother to tend to me on her own. She was 20, living in a place where she had no friends. Two years later, my mother was pregnant again, this time with my sister, Lori.

He was rarely home, and my mom had to take care of my younger sister, Lori, and me, sometimes for weeks on end, while my father did whatever men did back in the ’60s. He wanted to fit in and be successful. I can only imagine that he wanted to be rich so that he could take care of his tiny family.

My father once told me a story about how he came home one Friday and I had been a particularly difficult 4 year old, so much so that my mother couldn’t deal with me and had had enough. When he came home, she broke down and said that I had been a very bad boy . With that my father stormed over to the utensil drawer and pulled it out with such a fury that it crashed to the ground, utensil falling every where. He was looking for the wooden spoon.

He told me that I scampered up the stairs like a dog with its tail between its legs with him in pursuit until he grabbed me, threw me over his knee and beat me with in an inch of my life. After the “spanking” was over my mother came up to look at the damage and found welts and seriously bad bruising, he had hit me so hard that he broke the skin. She told him to come up and see what he had done.

He told me he was horrified with himself and never raised a hand to me again after that.

By 1966, my mother was struggling. She was 25 years old, raising two children mostly on her own, while the world around her was changing dramatically. It was a new era of female emancipation, rock music, and new freedoms. While my father was away, she happened upon an ad in a local newspaper looking for vocalists and musicians. The state of New York had just opened up bars and lounges to include live music, and agents all over the eastern seaboard were racing to put together bands to fill the sudden demand for entertainment in drinking establishments.

My mom decided she wanted to be in a rock and roll band on the weekends when my father was home.

She thought, “Hey, you can take care of the kids once in a while.”

That didn’t go down well with my father. He gave her an ultimatum and in 1966, when I was 5, my family disintegrated. I went with my father, and my sister went with my mother.

My Dad was an 8 mm film buff. He was always shooting movies. This was the last one he shot. It was of my mother leaving home forever. The end of my family.

As soon as she left, my Dad set to the task of finding some to take care of me. He had to go to work on Monday, so he paid a family a few doors down to take me until he found a more suitable part time foster family.

The moments in this first strange house are my earliest memories of childhood. Everything before and much of what came after remains blank, except for select things I saw there and other locations that burned themselves into my retinas. I didn’t realise it back then but this ride was only just beginning.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. (n.d.). Antisemitic legislation 1933–1939. Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved November 28, 2024, from https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/antisemitic-legislation-1933-1939

Smoky Lake and District Cultural and Heritage Society. (1983). Our legacy: History of Smoky Lake and area. The Society.