Shame and embarrassment were all I felt. I had been beaten senseless in my own backyard.

I sat in the living room, half-watching a television show, hoping to distract myself from the relentless throbbing in my face. But my mind kept drifting to my father’s imminent return—and the story I’d have to tell him about what had happened.

The swelling blurred my vision, and every breath through my mouth sent sharp pain where my new nose was. The bulky cast pressed awkwardly against my face, amplifying the discomfort. I wondered what my nose was going to look like when it was next revealed. Nothing felt bearable. No matter where i looked, half my scope of vision was impeded by a large slab of concrete slapped over the bridge of my nose. I had a small condo on my face.

I was supposed to go to school and skating the next day, but the pain was too much. I decided to stay home, telling myself a few days would make a difference. It didn’t. Lying down made the pressure worse, and standing wasn’t much better. Sometimes I would just rock back and forth on my hands and knees. I couldn’t find relief in any position except motion.

My upper lip cracked from the constant press of my tongue against it—a habit I had developed to distract myself from the pain. It worked for a while.

I stayed home the entire week. Days blurred into game shows, soap operas, and midday movies. I wandered around the house, avoiding mirrors and meals. Chewing made the pain flare, so I stuck to cereal and soup. I started giving myself continuous things to do. I figured if I was thinking about and doing other things, my attention would be diverted from wallowing in self pity.

By Friday, the pain had dulled and I had done, drawn and made things, but the anticipation of my father’s return made my stomach twist. I had spent the whole week rehearsing the story. I couldn’t tell him the truth.

Through a crack in the living room curtain, I saw his headlights pull into the driveway. The sky behind him was tinged with burnt orange, the remnants of a setting sun. The clear sky hung on stubbornly, but darkness crept at the edges, ready to envelop us. My heart began to pound, and the throbbing in my face returned with a vengeance. I scrambled to rehearse the lie one last time.

I switched off the TV and picked up the social studies textbook I had left nearby—just in case, I needed to re-enact a scene of study. From the window, I watched him walk up the backyard path, the same path where I’d been mashed days earlier. The tall fences lining our yard reminded me how they had hidden everything during the attack, sealing me off from the world while it happened.

The front door creaked open.

“Is anybody home?” His voice was unusually cheerful.

Panic set in. Should I stand and greet him? Stay seated? I couldn’t remember what I usually did. Why couldn’t I remember?

I stood slowly, feeling the weight of my swollen face, and stepped into the hallway.

The moment he saw me, his face twisted in shock.

“Oh my God.” His eyes widened. “What happened to you? Are you okay? When did this happen?”

I silently hoped he would keep asking questions. The more he spoke, the more time I had to settle into my lie.

I brushed past him into the kitchen and sat at the table, glancing around to make sure everything looked clean.

I hadn’t been eating much. The kitchen was spotless—no crumbs, no dishes. I had vacuumed earlier, stacked the newspapers, and made sure my room was tidy. The chili he made before leaving sat untouched in the fridge. I wasn’t going to give him any reason to get angry.

I took a breath and launched into the story in one long, breathless run-on sentence.

“Well, I came home later on Tuesday because I went to the Burger Baron to fill out a job application. When I came in, I saw someone through the curtain by the sliding door. I could hear scratching, and I thought they were trying to break in. I went outside quietly to scare them off. But when I came around the corner into the backyard, I got hit in the face. I think it was a pipe or something. I didn’t even see who it was. There was a lot of blood, and whoever it was ran away.”

I kept my eyes on the table as I spoke.

My father stared at me, dumbfounded. He looked panicked, and I imagined he was already wondering if the police knew anything. Maybe he thought someone would show up at our door.

“What did you do?” he asked, his voice hesitant.

I kept going, sticking to the script.

“Oh, well, as I was coming out of the backyard, a woman walking down the sidewalk saw me. I guess there was a lot of blood. She asked if I was okay. I told her no and asked if the damage to my face looked bad. She said yes and asked when you’d be home. I told her you were working late. She offered to take me to the hospital, so she drove me to the U of A. The doctor fixed my nose and put on this cast.”

I glanced up briefly. His face was unreadable.

“And that’s what happened.”

Silence settled over the kitchen.

My dad sat down at the table and started rifling through the mail. I couldn’t tell if he believed me, but he wasn’t asking more questions. I got up, ready to escape back to the living room.

“What did they say at school?” he asked suddenly.

“Nothing. I didn’t go this week. I was in too much pain.”

“Did you call someone and tell them you wouldn’t be coming?”

The first crack in my plan. I felt the panic rise.

“Umm, no,” I mumbled. “I thought it would be better if I just stayed home. I didn’t want anyone asking questions.”

He nodded slowly. “Did you go to the rink?”

“No.” I shook my head. “I didn’t want to fall and make things worse. I just want my nose to heal so I don’t look ugly.”

“Yes, of course,” he said quietly.

I could tell he was trying to process everything. He leafed through his Time magazine, but his eyes didn’t really focus on the pages.

“Well, I’m sorry this happened to you,” he said after a moment. “But thank you for stopping us from getting robbed.”

“Can I watch TV now?”

“Yes, go ahead. Do you feel like eating?”

Now that the pressure was gone, I realised how hungry I was. “Yeah. What’s for dinner?” I lingered by the kitchen entrance.

“I don’t know. Is there anything left?”

I told him I hadn’t touched much. The chili he made was still in the fridge.

“How about chili and toast?” he said, his mood lightening.

He hugged me tightly—something that didn’t happen often, then went on to warm up the food.

“I’m gonna watch TV now,” I said, leaving the room.

Having given myself permission, I sat down on the couch, silently congratulating myself. I had done it. I wasn’t the pathetic kid who got beaten up anymore. I was the one who saved the house at great personal cost. I was a hero!

I lived that lie for decades.

It wasn’t until I visited my father in Faro, Portugal, in 2010, that I finally told him the truth. We walked along the coast, and I told him everything. It had taken me 32 years.

That day, he told me that every time he heard “The Cat’s in the Cradle”, he thought about us.

…When you comin’ home, Dad? I don’t know when, but we’ll get together then, son. You know we’ll have a good time then…

The End of Skating

As it turned out, that wasn’t the last catastrophe I had to deal with while my father was absent.

I spent my 14th and 15th years in what felt like an endless cycle of training, studying, and working. I had no friends and had not learned how to be social at all. I had no one to hang out with and share the experience of growing up. I never got invited to anyone’s house, I didn’t go to birthday parties and I didn’t have a best friend. I was about as much of a freak as they come.

I liked girls but somehow earned a reputation for being “gay” because I was a figure skater. The girls stayed away. I had almost no self-esteem.

I wasn’t attracted to boys, so I was left confused—unsure of who I was supposed to be or how to navigate things socially.

I cycled through a few dead-end jobs. First, I washed dishes at the Burger Barn, then did the same at White Spot Restaurant. Eventually, I landed a job in the suit department at Woodward’s, the big department store in Southgate Shopping Centre—right near the rink where I skated.

It turned out to be a great job. I learned how to tailor off-the-rack suits and eventually was taught how to measure clients and then cut and sew a suit from a pattern that I created from the measurements—a skill I maintained for the rest of my life. It felt like an apprenticeship. I worked three to five hours on days I didn’t skate and two hours on nights I did. My schedule was relentless, but I started to have money in my pockets with which I bought record albums, gadgets, and clothes.

My skating coach was lured away from the city-owned rink I trained at to work at a private country club called The Derrick Golf and Country Club. To keep training with Mrs. Thirlwell, my dad had to join the club.

In a way, it was exciting. The club had bowling lanes, three restaurants, tennis courts, badminton, handball, and squash courts and indoor AND an outdoor swimming pool , with grass!” It was massive—and the skating rink had practically been taken over by the figure skating club. It was a whole new scene of competitive skaters.

For my dad, it was a chance to pretend he was wealthy. He justified the membership by saying he could meet potential clients there, and maybe—just maybe—we’d rise into a higher social class.

I didn’t really understand what he meant. All I knew was that I liked being able to visit the restaurant and order a toasted chicken salad sandwich and mushroom soup almost every day I skated. It was my favourite meal.

Sometimes I’d switch things up and order a beef dip and onion rings or a cheeseburger and fries, but a toasted chicken salad and mushroom soup? That was my go-to lunch.

I had taken a few more gold medals and worked tirelessly to stay ahead of my peers. In my 14th year, I began skating in a summer training program that ran from the day school ended until it started again. I spent my days entirely at the club, surrounded by skaters of all ages. There was one other boy and a group of girls, and we quickly formed a tight-knit clique. For the first time, I got to hang out with other people. It turned out we were all awkward. And then there were the skating moms—but that’s a story for another time.

When we weren’t on the ice, we got up to mischief around the club, finding hidden storage areas and turning them into secret clubhouses. In these secluded spots, we played games like spin the bottle, cards, and other games we made up—games we had no business playing. We did things that should have landed us in a lot of trouble, but as long as we showed up on the ice on time, no one seemed to care. The older, wealthier girls were the worst, often encouraging us to do things we weren’t entirely comfortable with, though we went along with it anyway.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Thirlwell’s personality had turned even uglier. She drove me relentlessly, berating me constantly and dishing out punishing physical discipline. “You’re the best of a bad bunch,” she’d say repeatedly, her words cutting deeper each time. Training with her became unbearable, and I started to loathe going to the rink altogether.

Then, during the summer of my fifteenth year, everything changed. One warm afternoon, as I was riding my bike home from the rink, I had a serious accident.

The neighborhood around my house was usually quiet, with very little traffic. Coasting along after skating, I enjoyed the warm summer breeze on my face as I approached an uncontrolled intersection. To my right, I noticed a car in the distance. It seemed far enough away, and in my mind, it was moving much slower than it actually was. it was still bright outside and I was carelessly confident I could make it across, I sped up to beat it through the intersection.

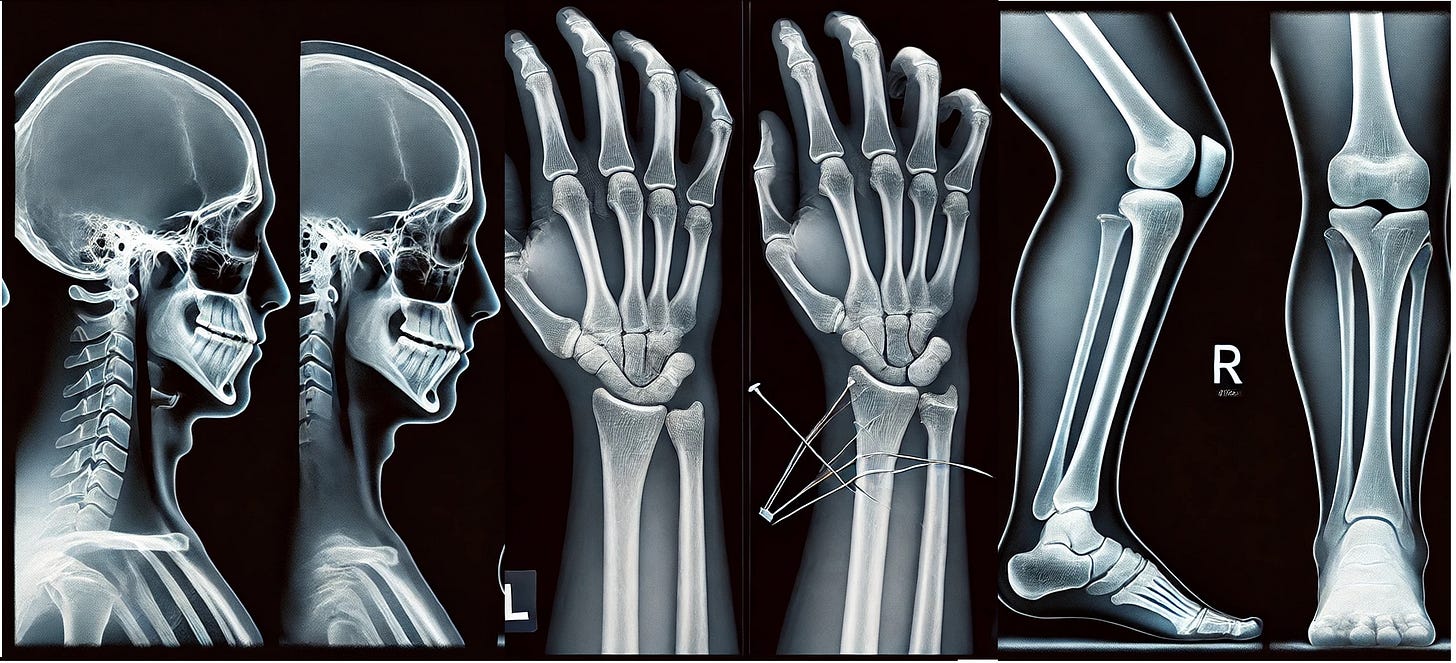

I miscalculated. The car reached the intersection faster than I expected, and I was broadsided. The sound of metal crashing and large thumping noises echoed in my ears as I was knocked off my bike, over the front right grill of the car and thrown partially under the wheel. I watched as the front right tire of the car rolled over my left wrist.

When I came to, a crowd of people had gathered around me. Just moments before, the entire area had seemed empty, and I couldn’t fathom where they had all come from. Did they all come out of the surrounding houses? My mind raced with confusion as I tried to process what had happened.

Instinctively, I tried to stand, but a sharp memory flashed in my mind—I had seen the car’s tire roll over my arm. Panic set in, and my first thought was about the watch my dad had given me for my birthday. I worried it had been crushed in the accident.

I looked down at my arm and tried to lift it, but something was terribly wrong. Instead of seeing the face of my watch, I could only make out the back of its buckle. My hand dangled lifelessly, flopping in unnatural ways, as if disconnected from my body. My fore arm looked warped, bent grotesquely into the shape of a Z. My head spun as I struggled to comprehend what I was seeing, but the shock numbed me to the pain.

I remember asking over and over, “Is my watch okay? Is my watch okay?” as a few onlookers stared, horrified. Someone gently lowered me to the ground and threw a blanket over me. The world started to flicker in and out as I fought to stay conscious.

The next thing I remember was being loaded into an ambulance. The sirens wailed as we sped toward the University of Alberta hospital. I was rolled into the emergency room, my surroundings a blur of bright lights and muted voices.

The next clear memory I have is waking up in a hospital bed, extremely woozy, my arm encased in a heavy cast.

The accident happened on a Monday, and as usual, my dad was away. When I regained consciousness, I was informed that I’d need to stay in the hospital for a while. The doctors explained that both the radius and ulna in my left arm had suffered two major fractures each and would need to be rebroken and reset with pins during surgery.

I don’t recall anyone asking me about my dad or where he might be. I assume they sorted it out behind the scenes after finding my identification in my wallet. Like so much of my youth, my memories of that time remain fractured and disconnected. What I do remember is that my dad finally showed up on Friday and arranged for a television to be placed on a swinging hanging arm at my bedside.

On Saturday, he returned with Mrs. Thirlwell. I recall them speaking with the doctor and agreeing that I could return to the ice—but only to skate laps until the cast came off in five weeks.

The cast was heavy and cumbersome, so they decided to modify it. My arm was positioned perpendicular to my body, with a portion of the cast extending under my armpit to support proper arm carriage while skating. I hated it, but I was told it was the best position for my arm to heal properly.

There was a lot of concern about the timeline leading up to the next competition cycle. I had just six months before my first Novice Men’s competition, and having won six consecutive gold medals, the pressure was immense. My coaches worried I would lose a significant amount of jumping power during recovery. I compensated with a lot of squats, flat irons and low level spins.

Before the accident, it had already been decided that I needed new custom-made skating boots. I took delivery of them shortly after returning to the ice and began the grueling process of breaking them in. New boots were stiff and took weeks, sometimes months, to break down correctly. Breaking them in was a painful process, but since all I could do was skate laps while my arm healed, it was determined this would help prepare them in time for competition.

I continued to skate figures using a different set of boots and blades. With little else to focus on, I used the time to excel in compulsory figures. Meanwhile, I skated laps in my new boots for hours, doing nothing but strokes, turns, and spins. About three weeks into this routine, while skating laps with my arm in a cast and breaking in the new boots, I felt a loud pop in my ankle and collapsed on the ice.

I couldn’t stand up. Taking off the boot was excruciating, and I was rushed to the hospital for an X-ray. The doctors discovered that the new ankle support, which included plastic inserts, had failed to break down properly. Because of the awkward position of my healing arm, I had placed excessive, repeated pressure on my right leg—my power leg—causing the posterior tibialis tendon to disconnect.

More surgery was required to place pins in my ankle, and I spent a week in the hospital recovering. When I left, I had a cast on my right foot and my left arm.

I was a mess both physically and psychologically. Literally broken.

I hated my life.