I’ve led a very mobile life. I can’t even recall how many times I’ve moved. Each move was driven by a series of circumstances that made it clear staying put wouldn’t bring the long-term satisfaction I was seeking. As a kid, my exit strategies were always rooted in dissatisfaction with how I was being treated where I was staying. As an adult, they were usually tied to the need to stay employed or find love.

Each family I stayed with left me with a different set of takeaways, none of which did anything to make me a better person. In fact, more often than not, they fueled a deep frustration and anger that I channeled into a fierce sense of independence. I started believing, very early on, that I didn’t need anyone’s help—not if this was the kind of "help" I was going to get.

I don’t want to be haunted by these memories, but I haven’t figured out how to leave them in the past. Sometmes they go away, but they’re always there, lingering in my subconcious, often resurfacing as nightmares that can only be subdued by smoking marijuana. When you smoke marijuana, you stop dreaming—or at least you stop remembering your dreams.

The Molsens

After I left the farm and went to Edmonton I was placed with The Molsens, a young couple with a five-year-old boy, Brett, and a new baby. Mr. Molsen, a music teacher, and Mrs. Molsen, a homemaker, provided a stable environment, and I even made a few friends while living with them. They had a comfortable lower middle class home for four in a sprawling community lost in the subdivisions of South Edmonton.

One of my clearest childhood memories whilst living with them is playing “Commando” with a group of boys I had befriended. Armed with sticks held widthwise in our mouths as makeshift knives, we crawled around like soldiers.

Then, at one point, someone appointed themselves team leader and we were all members of his squad. He barked orders at us, “go there”, “lie down”, “jump over that thing” and we dutifully did as our commander ordered until he got us to the bike rack at the school.

He said, “okay do this” and proceeded to reposition his stick in his mouth length wise. He then started spinning around the bike rack in a daring move. It didn’t last too long, he spun around the rack once, but on the second pass he picked up speed and the stick jammed against the bike rack and impaled him in the back of the throat.

All I remember is him jumping to his feet screaming at the top of his lungs, with the stick protruding from the back of his mouth wiggling as he screamed. We all ran away in terror to tell any adults we could find that something bad had happened. Our fearless squad leader was no longer fearless and kept screaming as he ran, stick wiggling as his eyes bulged out of his head. No one thought to take it out.

I don’t remember ever playing with those guys again.

Hiding Behind The Curtain

Fridays always followed a ritual and it was not different at the home of The Molsens. I would stand behind the curtain of the picture window in whichever house I was staying, my small bag packed, and wait for my dad. Sometimes he’d arrive right at 5 p.m.; other times, he could be up to three hours late. The waiting was nerve-wracking. All I wanted was to go home and spend time with him, but the uncertainty of when he’d come always left me on edge. Every minute that elapsed was one less minute I got to be at home.

During this particular week, two incidents left me feeling angry and upset. On Sunday night, after I had been dropped off, I overheard a conversation between the Molsens and my dad. They expressed concern that their son, Brett, felt threatened by me. They said someone needed to explain why I wouldn’t be treated the same way as Brett and why I couldn’t treat Mr. Molsen like a dad. I felt a wave of anger as I listened. The words stung, and I stewed over them all week, becoming more upset as the days passed.

Later that week, another moment pushed me further. I was in the living room when Mr. Molsen came home from work. As usual, there were kisses and hugs from his wife and son, followed by the customary fussing over the baby. They all huddled together on the couch, sharing their little world. I was nearby—either playing with something on the floor or doing homework; I don’t quite remember. Then Mr. Molsen turned to me and said, “David, can you go to your room now? We’d like to have some family time.”

“Family time.” The words cut into me like a knife. I stood up and obeyed, going to my room without a word. I left the door slightly ajar, just enough to see them through the crack. I watched as they shared their moments as a family, feeling an unbearable loneliness. The emptiness was overwhelming, and I struggled to hold back tears. It was one of the most isolating and painful experiences of my childhood. All that I wanted was to have some of that. To be part of a loving family. To be hugged.

When Friday finally arrived, all I wanted was to leave. I went through my usual ritual, standing behind the curtain and waiting for my dad. Time dragged on, and around 6:30 p.m., I was called to join the family for dinner, something I typically didn’t do on Fridays. Reluctantly, I sat down, but I wasn’t hungry. Anxiety grew as I started worrying my dad wasn’t coming. After excusing myself, I returned to my post behind the curtain, determined to keep my vigil until he arrived.

Then the phone rang, and I instinctively knew it was my dad. Mrs. Molsen answered and, after hanging up, came over to me. “David,” she said gently, “your dad won’t be able to make it tonight. He’s running behind but promised he’d be here first thing in the morning.”

I tried to ignore her. I didn’t want to accept it. I couldn’t stay there any longer—I just couldn’t. I wanted to go home. I wanted to be with my dad.

Then I blurted it out. My exit strategy from the Molsen household was to lose my temper and shout at her without a filter: "I don’t want to be here. I don’t like it here, I don’t want to live with you anymore."

Mrs. Molsen’s face changed, becoming dark and antagonistic. “Fine,” she said. “That can be arranged. I suggest you go to bed now and I’ll talk to your dad in the morning.”

The next day, my dad arrived, and the Molsens had “the conversation” with him. He was visibly angry at me as we left. When we got to the car, I got an earful of punishments. He told me he would have to take time off until he could find me another home. I was secretly happy to be with my dad every day until the situation was sorted out. He couldn’t be mad at me forever, right? It turns out that I was kind of wrong about that. He stayed grumpy with me the whole time. I had gone from one unloving situation right into another.

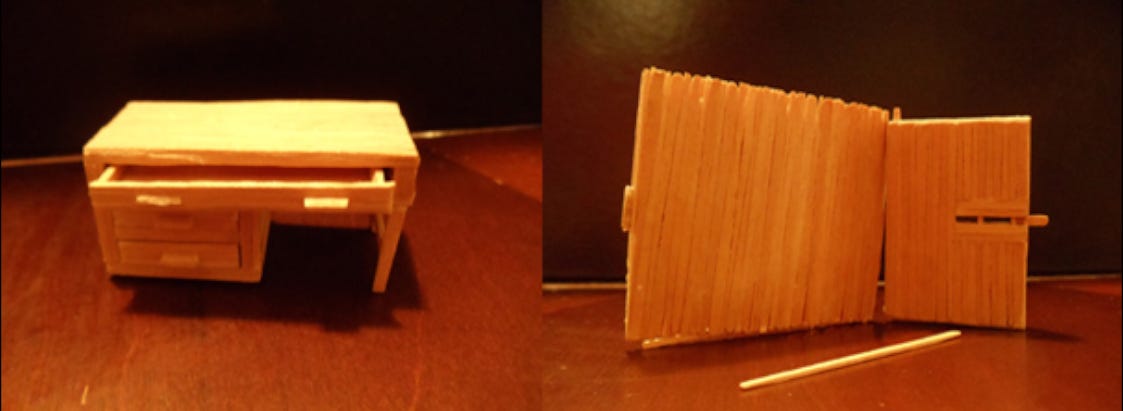

I spent most of my time in my room working on my toothpick models. I loved it because it provided an escape from the loneliness and unhappiness, allowing me to create a world of my own while holding onto some of my fondest memories of time spent with my dad.

Lost in Miniature Fantasy

During the summer of my 10th year, just before we moved to Edmonton, my dad took me to Disneyland in California. It was the best trip ever. I got to hang out with my dad, fly on a plane, stay in a hotel, eat in restaurants and wait for hours trying to get on rides like Jungle Cruise and Mr. Toads Wild Ride. But I think the attraction that had the most impact on me was The Enchanted Tiki Room. It was a truly magical place for me as birds and flowers came alive and sang songs in a huge colourful room made of bamboo and exotic plants.

I was so inspired that when we came back from the vacation I started building an amusement park of my own out of toothpicks on my worktable in my bedroom. It became the biggest model I was ever to make as a kid. It had a pool, a monorail, a hotel with foyer and a grand staircase leading to two hotel rooms. Each room had a door that locked with a sliding mechanism that could only be opened using a toothpick key. I built chairs, desks and and cabinets, all of which were fully functional with drawers and doors and sliding parts.

I was always happy making models. I disappeared into a place where anything was possible. That two weeks I spent at my Dad’s place while he sorted out a new place for me to live was like a holiday. He had to drop me off at school and I was going to figure skating lessons four times a week, Tuesdays and Thursdays from 4 pm until 6 pm and then Saturdays and Sundays in the morning. He was picking me up and dropping me off, I loved it. I though how much I would love to have this all the time. The rest of the time I got to watch tv or hang out in my room building my toothpick masterpiece.

Everything was great… until I spilt a small bottle of silver model paint on the carpet.

My dad loved to build models and introduced me to the hobby very early on. I used to watch him for an hour or two on weekends while he worked his magic on a store bought racing car kit. His attention to detail was immaculate. He even went so far as to paint all the bolts on the engine.

My first attempts were not so beautiful. I was a kid and thought that the faster I finished it the more I would be like my dad. But after many years, model making became one of my primary fascinations and I started to take the same painstaking effort I learned from my father. I made models of everything including the bus I now live in.

My dad always told me to make sure the caps on the paint bottles were tightly secured. But I was eleven and rarely listened. I would place the cap on top but never twist it fully shut. Over time, the paint around the edges would dry, creating enough adhesion to hold the cap in place. You could even pick up the bottle by the cap, and it seemed secure—until it wasn’t.

One day, I learned the hard way. As I moved a bottle from one spot to another, the cap stayed in my hand, but the bottle didn’t. I watched in slow motion as it slipped free, tumbled onto the table, and landed upside down on the brown wall-to-wall carpet in my room.

My heart raced, my head pounded and I felt very very hot. My impulse was to take a rag and start trying to rub it out which only made the situation worse. In no time I had a big silver smear where a small amount of paint had landed. I figured the best thing to do was cover the stain with my shoes, so I took all of my shoes and placed them in a straight orderly line covering the stain. Of course the stain was in the middle of the carpet and not in a place where one normally places shoes.

I didn’t know what to do. Things seemed to be getting better with my dad and I since I had left the Molsens house but I knew that this was going to change everything. After I hid the damage I went into the living room, turned on the tv and sat in my rocking chair. I rocked back and forth quite quickly thinking that maybe the problem would go away if I let it dry and tried again to wipe it up.

My dad sensed something was wrong and asked me directly. I confessed—I had spilled paint on the carpet. Without a word, he bolted down the hallway and into my room. I cautiously followed him down the hallway.

He grabbed a couple of small bottles of paint thinner I had lying around, emptied them onto a rag, and started scrubbing the stain. But it wasn’t enough and just made things worse. When my dad was angry, the safest thing to do was to stay small and out of his way.

It was still early in the day when he ordered me to sit in my chair and wait. No TV. Just wait.

I went back to my chair and rocked back and forth nervously while he went out to buy more solvent. The minutes felt like hours. When he returned, he carried a giant bottle of thinner and went straight to work on the carpet. He scrubbed furiously, determined to erase the mess, while I sat in the living room, petrified, rocking like my life depended on it. I couldn’t stop imagining what punishment might come next.

Hours later, he finally finished. Without a word about the stain, he turned to me and said, “Go to bed. No dinner.”

The smell of paint thinner hit me as soon as I walked into my room. It was overwhelming. I crawled under the blankets, the heavy fumes making my head spin. I fell into a deep, uneasy sleep, even though it was still so early.

When my father’s temper flared, it was quick, sharp, and unforgiving. He never hit me, but his anger isolated me emotionally in ways that cut just as deeply. It was a pattern I had come to know all too well. His frustration with my mistakes, big or small, felt constant, and the stress began to manifest physically.

I developed nervous tics that grew worse in tense situations. I coughed frequently, even though nothing was wrong with my chest. I constantly stretched my neck like a pigeon and blinked hard. I didn’t even realize I was doing it until one day, during one of his outbursts, he snapped, “Why are you doing all that?”

His words jolted me, and suddenly, I became hyper-aware of every cough, stretch, and blink. Being conscious of it only made it worse. Before long, I found myself sitting in front of a doctor, undergoing tests to figure out what was wrong with me. I was not there when the proognosis was delivered so I have no idea what was said or what the course of action was.

Not too much later, his anger surfaced again—this time, not within the confines of our home but in the polished, intimidating office of a lawyer.

The Lawyers

My dad had filed for divorce, and I was required to meet with some lawyers. He had known about this meeting for a while and had prepared me for it in his own way.

“They’re going to ask if you want to see your mother,” he told me repeatedly. “You’ll say, ‘No, I don’t want to see my mother.’”

He drilled this into me for days, making me repeat it over and over until the words felt like they belonged to someone else.

The day finally came. On the drive to the fancy law offices, he kept asking me what I was going to say. Each time, I repeated the script I’d been given. I wanted to make him proud—or at least avoid making him angry.

When we arrived, the receptionist led us to a polished foyer where I was told to wait. My dad was invited into an office by three men in suits. The door shut behind him, leaving me alone in the silence of the waiting room. My stomach churned, and my legs felt like jelly.

After what felt like forever, the door opened. My dad stepped out, and one of the men turned to me with a kind smile.

“David, would you come in, please?”

I glanced back at my dad, hoping he’d follow. Instead, he took a seat and said firmly, “Remember what we talked about.”

The door closed behind me, sealing me in the room with the three men in suits. One of them offered me candy, which I quickly grabbed without hesitation.

Then one of the men leaned forward and spoke in a calm, reassuring voice.

“David, there’s nothing to be afraid of. We just have a few questions for you. It’s important to know there are no right or wrong answers. We just want to understand how you feel. Can you do that?”

I nodded, clutching the candy in my hand.

And then the first question came.

“Do you love your mother?”

There was a long pause. The words my dad had drilled into me didn’t fit this question. I struggled, my mind racing to make sense of what I was supposed to say, but nothing came. Finally, I answered honestly.

“Yes, I love my mom.”

The man nodded and asked the next question.

“Do you miss your mom?”

My stomach tightened, and I felt a knot forming in my throat. The rehearsed answers I had memorized didn’t work here either. Once again, I spoke the truth.

“Yes, I miss my mom.”

The third and final question followed.

“Would you like to spend Christmas or the holidays with your mom and your sister?”

I froze. Tears welled up in my eyes. I knew exactly what I was supposed to say, but I couldn’t force the words out. Instead, I whispered, “Yes.”

In that moment, I wasn’t thinking about the consequences. I was thinking that maybe, just maybe, if I said the right thing, something magical might happen. Maybe my parents would get back together. Maybe we’d all spend Christmas together—my mom, my dad, my sister, and me.

All I wanted was a family Christmas.

And with that, it was done.

“Okay, David, thank you very much. You can go back out now. We just need to talk to your dad for a few minutes. Do you want more candy?”

I nodded, took the offered candy, and walked back into the waiting room. My dad stood as I approached, his face unreadable. He brushed past me and entered the office without a word. The door clicked shut behind him, leaving me in an uneasy silence.

Then the shouting started.

At first, I couldn’t make out the words, just the muffled cadence of voices. But my dad’s voice grew louder, angrier, spilling through the heavy office door. My hands began to shake, and my stomach churned. I knew I had failed. I knew I was going to be in trouble—again.

Suddenly, the door flew open, slamming against the wall. My dad stormed out, his expression dark and furious.

“Come on, we’re going,” he barked.

I hurried after him as he strode toward the elevator. The air between us crackled with tension. He pressed the button, his jaw clenched, his silence louder than any words.

We rode the elevator down to the parking lot in complete silence. I barely breathed.

Once we were in the car, he exploded.

“What did you say? We talked about this! You knew what to say—why didn’t you say it?”

Everything inside me felt tangled and tight. My throat swelled as I tried to explain. My pigeon neck tick started, chin moving back and forward, shoulders being pulled back as if I was trying to get something off the back of my neck.

“They asked if I loved Mom,” I whispered. “We didn’t practice that question.”

He didn’t respond. The rest of the ride home was suffocating, the kind of silence that made every second stretch.

It was Monday. My dad had taken the day off work for the meeting. We were living in the basement apartment of Alex and Glenda Murphy, friends of his who had recently had a baby. They needed help with the house payments, and my dad thought it would be a good arrangement—us living there, with the family upstairs able to keep an eye on me when he wasn’t around. No more getting picked up and dropped off. This was our place.

He left the next morning for work and didn’t come back until Friday night. I felt as though he was going to stop loving me. It was a hard week and the Pigeon neck and blinking just got worse.

Looking back, the pigeon neck wasn’t just a nervous tic; it was a sign of the pressure I was under. The more one tries to suppress bad feelings, the more they rise to the surface in unexpected ways.